One hundred years ago, a fireproof swimming pool burned to the ground at Summit and 11th streets in Little Rock.

As we learned Dec. 11, the Joyland building held the 50-foot indoor pool plus a roller rink and a dance floor/basketball court. Opened in 1914, J.W. Lippincott's innovative rec center was cited in the press for being an engineering marvel and free of sharks.

During its first years, newspaper society columns mentioned Joyland as the site of parties; the roller-skating, dances and basketball league drew off-season crowds; and Lippincott's frequent large retail advertisements suggest he had plenty of revenue coming in.

But after a teenager died at the pool in 1916 and his family sued, Lippincott stepped away from active management. A new proprietor, Nick Schmitt, took over. His penchant for promotions, including contests and special events — think, roller-skating bears — carried Joyland through the buildup to World War I.

But with the nation at war, all forms of recreation became suspect (even baseball). Patriots were supposed to be working. Federal agents swept Joyland when they raided businesses that seemed likely to attract draft-dodging "slackers."

And we can read in a concurrent steep decline of society notes in 1918 the shadow of the great influenza pandemic that would eventually kill about 7,000 people in the state (according to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas). Those deaths included soldiers at Camp Pike. Soldiers, who were among Joyland's target clientele. So times were tough for Schmitt.

Under the supervision of the U.S. Public Health Service, including officer Dr. Jacob Casson Geiger, the flu brought restrictions that historians today have characterized as mild: business curfews, limits on the size of public gatherings, canceled parties and temporary closures.

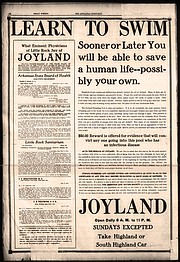

Schmitt soldiered on, advertising Joyland's sanitary practices, the electrically purified water he changed daily, the free bar of soap that now accompanied the swim suit rental, towel and shower bath for your 35-cent pool admission fee.

Two days after federal agents arrested any man who couldn't produce his Selective Service registration card on the spot, a narrative ad or, perhaps, puff piece in the Aug. 31, 1918, Arkansas Democrat mentioned that soldiers liked to swim at Joyland, which was larger and more sanitary than the "ole swimmin' hole": "Here special classes are put on every afternoon and evening for men and women, and little kiddies, too, and Joyland has passed the stringent requirements of the public health service."

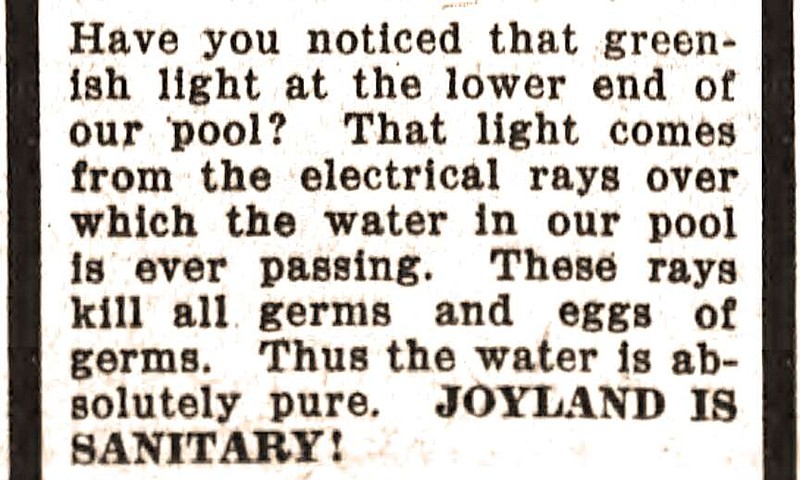

Did the public know that the greenish light at the lower end of the pool was electrical rays over which the water in the pool was ever passing?

"These rays kill all germs and eggs of germs."

NEW MANAGEMENT

It's easy to read a decline in conditions at Joyland in a rising number of classified ads reporting items stolen in its dressing rooms. In April 1920, another new proprietor stepped up, apparently leasing the facility from Lippincott and partners. Wilbur G. Scougale, a former Missouri Pacific clerk and 16-year resident of the city, took a five-year lease on the building. He did not last that long.

After a few retail ads, he confined his advertising to cheap one-liners in the Arkansas Gazette City Notes columns.

Petty thefts continued. In July, Scougale hired "Mrs. Miller," police matron, to monitor the ladies rest room and chaperone girls.

In June, he made an embarrassing visit to Judge Harry C. Hale's municipal court. Scougale had bought a bulldog from Reuben White, enterprising white youth. White sold him the collarless pet without bothering to look for its owner. He was Carl Beeler, 3020 Arch St. Hale fined Reuben $25 and sentenced him to 30 days on the county farm. Hale ordered the dog returned to the owner, whereupon Beeler sold it (again) to Scougale.

MORE NEW MANAGEMENT

Whether Scougale dropped his lease or was dropped I don't know, but in summer 1921, A.L. Herbert and W.R. Herbert took over Joyland. They charged adults 50 cents and kids 35 cents. They retained the right to refuse admission or eject objectionable characters — which suggests there had been some under Scougale.

They tried amateur swimming and diving contests. And "water clowns, provided by the management, will take part in the fancy diving and swimming exhibitions." Professional swimmers were not allowed to compete.

In September, a one-line ad announced that "Mrs. Herbert, a mother" was always near the pool to chaperone girls and ladies. But business was not good. By Dec. 28, 1921, Joyland was in receivership.

Nick Schmitt leased the place for a few months in summer 1922, renaming it The Highlands. He announced that admission fees were the "pre-war" price — 35 cents.

In October 1922, new owners from Dallas, E.G. Kemper, O.A. Fuqua and W.W. Mears, began renovations at Joyland. Roller-skating returned Nov. 1 with a live orchestra, and dancing opened in December. Kemper was installing a $10,000 "interchangeable lighting system." I think that means light bulbs.

He moved to Little Rock, too, into a house attached to the western wall of Joyland.

Kemper tried contests and stunts that fall and winter, including a "tacky party" — a costume party. In November, he ran a contest to find the most popular girl. Every paid admission to roller-skate included 10 votes.

In February 1923, he hosted a walking contest between Dan O'Leary, 82, veteran pedestrian, and girls on roller-skates. The girls won. A man named Harold Dean broke a leg.

Kemper added a $5,500 furnace, $6,000 in rink equipment and updated the pool laundry for the 1924 season. In October, he bought the property at the corner of 11th and Summit Streets diagonally opposite the rink, where the well and pump were.

INFERNO

Page 1 of the Dec. 9, 1923, Gazette delivered unexpected news: Joyland was destroyed in a five-alarm fire Dec. 8.

The Gazette reported, "Less than three minutes before the discovery, the last patron had left the building. The afternoon crowd of children had been exceptionally heavy, according to Mr. Kemper, and had the fire occurred a few minutes earlier, a tragedy might have occurred."

Two Black employees, Joe Yeager and Mose Bowman, noticed smoke coming from the basement and rushed down with extinguishers. Flames drove them back. Not more than two minutes later, the floor collapsed.

The building was a loss when the first companies arrived, and firemen concentrated on saving frame houses to the west. They were scorched by wind-driven flames, which charred telephone poles, too. Fire Chief Charles S. Hafer commended some nameless boys he assumed were Boy Scouts. They helped hold the hoses, he said.

Kemper's home was gutted. Firemen did manage to put out a fire on the roof of the next house over, occupied by Miss Minnie Chick.

The report added, "For a time it was believed Mr. Kemper's 2-year-old son had been lost in the flames. He and his wife were assisted in a frantic search by neighbors and had given up the child for lost, he said. They later learned that a Negro woman had taken the child from the burning house to a store at 12th and Summit."

Kemper estimated his loss at $60,000 on which, he said, he carried $18,000 insurance. But in July 1924, he sued 16 insurance companies, for $25,000 total. The insurers claimed that he had stored gasoline at the swimming pool in violation of their policies. But in October that year, 11 insurers settled, handing over 90% of his demand.

That news was the end of reports about Joyland in the Gazette and Democrat, so I don't know how he fared in the other five suits. Fortunately, we don't really care, do we?

Other amusement companies would co-opt the name Joyland, beginning with Joyland Park at 18th and Railroad streets in May 1928. But none of them could boast about their fireproof pools.

Email: cstorey@adgnewsroom.com